Story told by Jason Nicholson with help from Margaret (Molly) Kenneth FNP-C & Wesley Kerr MD-PhD

I feel proud, happy, accomplished, annoyed, and ashamed when I think about World’s Toughest Mudder (WTM) 2016. I’m proud to say that I completed thirteen laps/65 miles, finished the 24-hour race, and placed 95th overall out of 1,251 athletes. Considering all that went wrong, my performance was outstanding. But given everything that followed, I have a seriously different perspective.

Two days after the race I went to the Las Vegas emergency room in a lot of pain. The ER doctors admitted and placed me in the ICU with exercise-associated hyponatremia (EAH), rhabdomyolysis, and kidney failure. My blood sodium level was dangerously low and my creatine kinase test (a measure of muscle breakdown) was 148 times the normal level. I was in kidney failure and my blood was overloaded with toxins. I spent four days in the ICU and a week total in the hospital and while I have technically recovered, my body is more prone to cramps and less tolerant of extended activity.

I went in well trained, with a plan of how much Tailwind and water I needed to consume to support my effort. I was taking in about 1 liter of water with 400 calories of Tailwind per lap (¾ scoop per 12 oz)and an additional liter of water. I have since learned that endurance athletes should “drink to thirst” instead of drinking a calculated amount. Overconsumption of fluids is the biggest risk factor in dropping blood sodium levels to the point that it causes exercise-associated hyponatremia (EAH) (Rosner & Hew-Butler, 2016). In EAH, the fluid surrounding the cell is diluted, so more water is pushed into cells to balance the concentrations inside and outside the cells. As the cells get overloaded, they swell. As a result, your whole body swells including, most noticeably, your hands and feet. Other early signs of EAH are nausea and vomiting, weakness, dizziness, and lethargy (Rosner & Hew-Butler, 2016). Left uncorrected, or treated incorrectly, EAH can cause fluids build up in the lungs and brain cells to swell which can lead to seizure, coma and sometimes death. In fact, in his book Waterlogged, Dr. Tim Noakes describes multiple deaths that occurred in EAH patients that were wrongly treated with copious IV fluids that were more dilute than blood (hypotonic).

On lap 3 I took the cold swim penalty at Everest which resulted in severe cramps and me swimming without the use of my legs. Later in Blockness, my quads locked up in the water for 5 minutes or so, just like my calves did earlier in the lap. I had minor cramps all over my body for the remaining 21 hours of the race. I was in a lot of pain after the cramping started and throughout the rest of race, but I wasn’t quitting. I was finishing. What I didn’t know was that all those cramps were damaging my muscles, so toxins from inside muscle cells were released into my blood faster than my kidneys could push them out. When those muscle toxins build up, they damage the kidneys, much like the way a sink clogs with hair. Rhabdomyolysis is the presence of high levels of muscle cell contents in the blood, muscle aches/weakness and dark urine that can look like blood. Left untreated, rhabdo can cause irreversible and potentially fatal kidney failure.

I used Ibuprofen on course to treat my pain. Please, don’t judge me too hard here. I have good discipline but the cloud of the pain and not thinking it through caused me to look for a way to cope. I carried the Ibuprofen in my pack and it was refilled by my pit crew each lap which means it was always readily available; this contributed to my impulsivity. I was pretty desperate so I ended up taking almost the full daily dose (3000mg/15 tabs) in about twelve hours. Once I realized how much I had taken and it wasn’t helping, I quit taking it. Still, it was too late. Ibuprofen restricts the blood flow to your kidneys, whereas acetaminophen (Tylenol) has much less effect on your kidneys. A recent Stanford study demonstrated that use of ibuprofen during an endurance doubled the chance of acute kidney injury when compared with placebo (Lipman et al., 2017). In fact, because of the associated reduction of blood flow to the kidneys, my use of ibuprofen contributed directly to the development of life-threatening EAH, rhabdomyolysis and renal failure (Baker et al, 2005).

Even with all that was going wrong and the pain I was in, I still kept going. I was physically moving well enough to pass the medical check and I was able to answer the questions at the neuro check. I was determined to finish. I finished the race with 65 miles. I was glad to be done. I was in pain but there was a relief of being done with the race. I slept on and off Sunday. I urinated once after WTM and then stopped urinating. Monday evening I was vomiting. By Tuesday it was crystal clear I needed help. I couldn’t urinate, the abdominal pain was unreal and my body was continuing to swell. I had no idea, until months later, reading Waterlogged how seriously ill I had become.

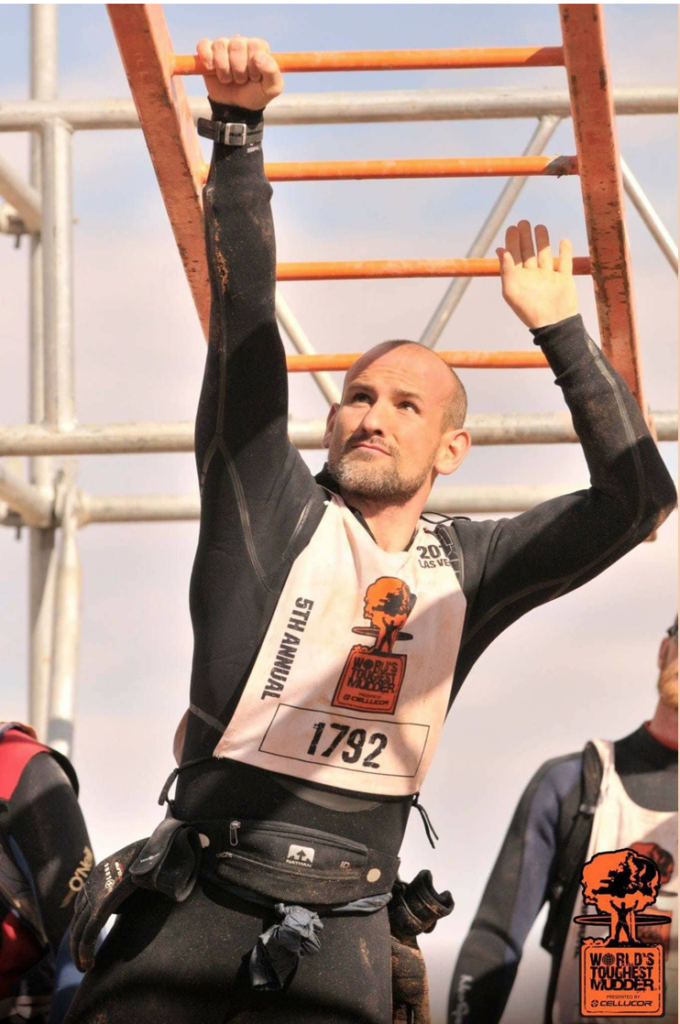

Photo cred: Cathy McDonald

The key takeaways from my experience are:

- Drink to thirst. Thirst is your bodies way of telling you that you need fluids. Drinking ahead of thirst came about because the influence of the Sports Drink industry on endurance sports. (Noakes, 2012)

- Ibuprofen/NSAIDs have no place in endurance events. It puts an extra load on your kidneys by restricting the blood to your kidneys. Your kidneys are already under extreme load. Don’t make it worse.

- Recognize that exercise-associated hyponatremia (EAH) is common in endurance events to some degree. Early signs include swelling of hands and feet, headache, nausea/vomiting, change in personality. Later signs are a debilitating headache, coma, seizures, and death.

- If you have time, read the full article.

References:

Lipman, G., Shea, K., Christensen, M., Phillips, C., Burns, P., Higbee, R., … Krabak, B. (2017). Ibuprofen Versus Placebo Effect on Acute Kidney Injury in Ultramarathons: A Randomised Control Trial. Emergency Medicine Journal. 34(10):637-642.

Noakes, T. (2012). Waterlogged. The Serious Problem of Overhydration in Endurance Sports. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Rosner, M. H., & Hew-Butler, T. (2016, January 13). Exercise Associated Hyponatremia. UpToDate. Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/exercise-associated-hyponatremia

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints and official policies of Mud Run Guide LLC, or their staff. The comments posted on this Website are solely the opinions of the posters.

Leave A Comment